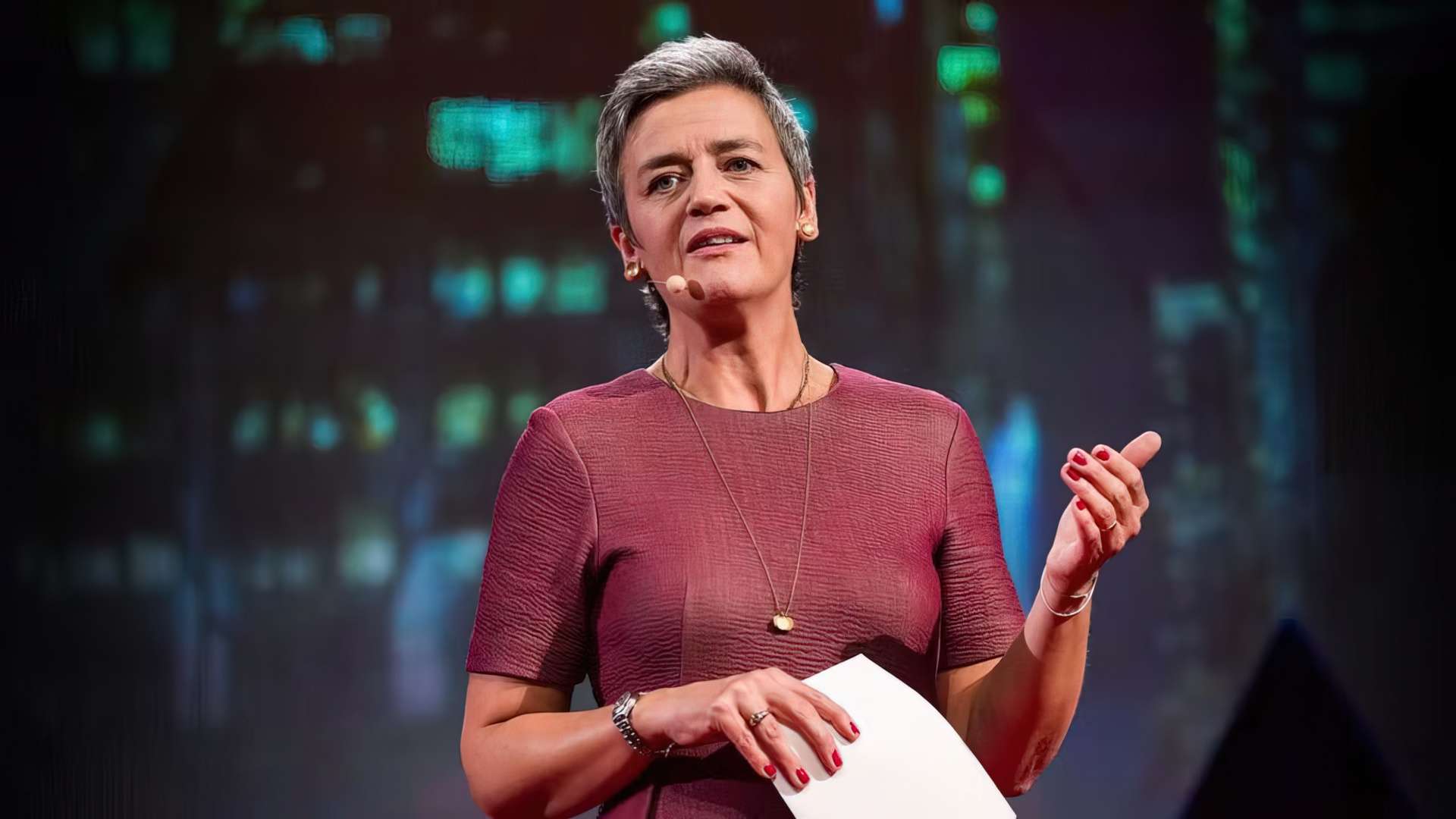

EU big tech regulation could happen sooner than expected. The EU has set a goal of enforcing the Digital Markets Act (DMA) by spring 2023, Commission executive vice president Margrethe Vestager announced at the International Competition Network (ICN) conference last week. Previously, Vestager said that the antitrust legislation, which will establish a new regulatory framework to limit big tech’s power, could go into effect as early as October of this year.

“The EU big tech regulation DMA will enter into force next spring and we are getting ready for enforcement as soon as the first notifications come in,” Vestager stated at an ICN speech. The EU’s Competition Commissioner, Margrethe Vestager, has said that the Commission will be prepared to take action against any violations committed by “gatekeepers,” which include Meta, Apple, Google, Microsoft, and Amazon — as soon as the legislation is published, TechCrunch reports.

What’s in the EU big tech regulation DMA?

The DMA will disrupt the industry models used by many of the world’s tech behemoths if it is adopted. For one, it might be necessary for Apple to start allowing customers to download software from outside the App Store, which Tim Cook has opposed because sideloading may “ruin” the security of an iPhone. This might mean that WhatsApp and iMessage must interoperate with smaller platforms, a policy that might make it more difficult for WhatsApp to enforce end-to-end encryption. Last year, Instagram removed the disappearing photos and videos feature due to EU regulations, next year Meta could remove the app itself from EU territories.

The EU big tech regulation DMA, which is still awaiting final approval from the Council and Parliament, refers to companies with a market capitalization of more than €75 billion that also own a social platform or app with at least 45 million monthly users. The DMA rules provide for penalties of up to 10% of a company’s worldwide turnover in the previous financial year if it is found to be non-compliant, with a penalty of 20% imposed in the case of a repeat violation.

In accordance with the DMA, gatekeepers have three months to notify the Commission of their status, followed by a two-month waiting period for confirmation from the EU. We won’t start seeing real fights between the EU and the big tech until the end of 2023, owing to the long DMA enforcement wait time and the delays.

“This next chapter is exciting. It means a lot of concrete preparations,” Vestager explained. “It’s about setting up new structures within the Commission… It’s about hiring staff. It’s about preparing the IT systems. It’s about drafting further legal texts on procedures or notification forms. Our teams are currently busy with all these preparations and we’re aiming to come forward with the new structures very soon.”

Pushing back the EU big tech regulation DMA’s enforcement might provide the Commission more time to prepare, but if it fails to address any major infractions that occur between now and when the DMA becomes law, the delay may be used as a pretext for criticism.

Many of the world’s most well-known IT firms maintain significant lobbying teams in Washington, and they have been stressing the dangers of such legislation on successful American businesses. However, many US lawmakers are also attempting to curtail Big Tech’s abilities, with bills now being considered by Congress that would do so. The DMA now faces definitive votes in the European Parliament and ministers from all 27 member states after negotiations were concluded.